Let me

begin with a confession: I’ve never much

liked The Wizard of Oz.

I refer,

of course, to the 1939 movie of that name – not to L. Frank Baum’s 1900 novel

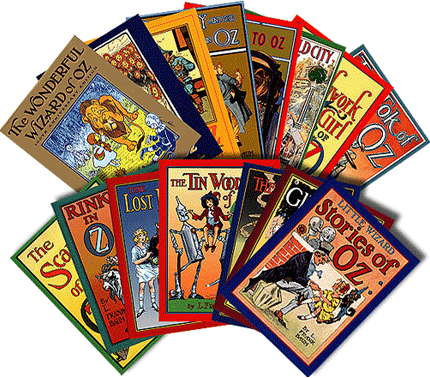

(properly titled The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) on which it is based, or to the still wonderfuller series of Oz books

that followed it.

I began

reading the Oz books in 1970, when I was six, and had acquired most of them (the

original ones by Baum, I mean) by 1972.

They were among my very favourites as a child – probably second only to C.

S. Lewis’s Narnia books. (Indeed, I suspect

I owe my east/west dyslexia to the early influence of the Oz books’ famous map,

which had east on the left and west on the right – just where my brain still

thinks they should be.) I had definitely

read at least Wizard and Ozma when I first saw the 1939 movie;

since I saw it in a theatre (we didn’t have a tv at that time), that must have

been either later that year or some time the next, as the film was re-released theatrically in 1970 and 1971.

Thus the

books, not the movie, were my introduction to Oz (though before seeing the

movie I did already know most of the songs, for somewhat odd reasons I’ll

explain in a future post).

So I mean,

it’s not as though I didn’t enjoy the movie.

Certainly the Scarecrow and the Witch were well done, and I did

generally like the songs. But I found

the film patronising and corny and talk-down-y in a way the book is not – with

the inane “Lollipop Guild” and the idiotic refrain “Lions and tigers and bears,

oh my!” being especially annoying. Dorothy

seemed more helpless and less resourceful than her counterpart in the book,

despite being older; and Billie Burke’s simpering Glinda was an insult to Baum’s

dignified sorceress (Oz’s equivalent of Galadriel should not coo and gurgle).

Making

Glinda the first person Dorothy meets in Oz, rather than (as in the book) the

last, also creates some problems. If the

one person who knows how Dorothy can get back to Kansas is now one of the

first, rather than one of the last, people she meets in Oz, then Glinda seems

to be simply withholding crucial information for no good reason. (Also, does Glinda know that the Wicked Witch

can be destroyed by water? If so, that

first meeting would have been a handy occasion on which to mention it – or

better yet, to toss the bucket herself when the Witch makes her appearance.)

As for the

Witch, having her show up repeatedly in person before Dorothy gets to her

castle gives her more opportunities to be scary, which is good, but it makes

less sense: if she can just pop up wherever Dorothy is, why does she never try

to kill Dorothy directly? It’s as though

Palpatine were to stroll into the Mos Eisley cantina in Episode IV, make a

threatening speech to Luke, and then stroll out again without doing anything.

The film also

left out the green spectacles, thus negating the whole theme of the Emerald

City’s fakery; and softened the original by having the Wizard ask for the

Witch’s broomstick rather than, as in the book, plainly telling Dorothy to kill

her (though the change could be redeemed if we interpret it as a responsibility-evading

bureaucratic euphemism on the Wizard’s part rather than as a

don’t-scare-the-kiddies euphemism on the filmmakers’ part). And the film couldn’t even leave alone the iconic

line “I am Oz the Great and Terrible.

Who are you and why do you seek me?” but had to change it to “I am Oz

the Great and Powerful. Who are you? who

are you?” (I suppose the change from

“terrible” to “powerful” was driven by concern to avoid the modern connotation

of “lousy” – though I’m glad that Peter Jackson didn’t scruple to have

Galadriel call herself “beautiful and terrible” in the Lord of the Rings films just as she does in the book. In any case, having Oz ask the same question

twice seems pointless.)

It also

bugged me (and still does) that the Cowardly Lion was just a man standing

upright in a suit. (Was this an

inevitable constraint, given 1939 sfx technology? Well, it’s a hurdle that the 1902 stage

production had managed to surmount.) Moreover,

Baum describes the yellow brick road as looking like a real road: in places

“rough” and “uneven,” with bricks “broken or missing,” leaving “holes that Toto

jumped across and Dorothy walked around.”

It should look like the crumbling elven road in The Desolation of Smaug (only, well, yellow), not like an expanse

of shiny plastic as in the movie.

Alissa

Burger strangely contrasts Baum’s version, which apparently “romanticizes the

Kansas prairie” and “the safety of home,” with the MGM version, which through

“its Depression-era setting” reminded audiences that “home was precarious, with

the family farm economically threatened.”

(The Wizard of Oz As American Myth,

p. 157) This is a bit puzzling. (Read the

first chapter of Wizard and see if

you think Baum is romanticising Kansas.) The farm

in the movie is a decent-sized and moderately prosperous concern, with a number

of farmhands, compared with the book’s drab and miserable farm with a one-room

house and no apparent employees. It is

Baum’s farm, not MGM’s, that seems economically precarious (as indeed it proves

in the later books when the Gales are unable to pay their mortgage). The 1930s were not the only period of

depression in u.s. history; Baum in 1900 was writing in the wake of the fairly

severe depression of 1893-1898. As for

“the safety of home,” in Baum’s book the Gales’ house is, y’know, destroyed by a tornado; in the movie, by

contrast, the destruction is only a dream.

Which

brings us to the film’s worst departure, which, of course, is having the whole

story turn out to be Dorothy’s dream – something that is decidedly not the case

in the book. Baum does say elsewhere that “in a

fairy story it does not matter whether one is awake or not,” but I suspect few

readers will agree. (Moreover, if

everything is reset at the end to the status

quo ante, then Miss Gulch’s threat to Toto is still in effect, so why isn’t

Dorothy worried?)

The film’s

protagonist was also not my image of Dorothy, though this isn’t really a case

of infidelity to the (first) book. Judy

Garland’s Dorothy, with her long dark braids and solemn demeanour, was based

(loosely) on W. W. Denslow’s depiction in the first book; but in all the later

books, illustrated by John R. Neill, she has shorter, lighter hair and a more

spirited attitude. Neill’s Dorothy is

admittedly a bit too glamorous and fashionable to be plausible as the ward of

two dirt-poor farmers in a one-room house on the prairie; but to my

six-year-old male eyes she was more appealing than Denslow’s dowdy, somber Dorothy. Baum’s wife

Maud incidentally shared my preference: “I

have always disliked Mr. Denslow’s Dorothy.

She is so terribly plain and not childlike.” (quoted in Michael Patrick Hearn, The Annotated Wizard of Oz, p. xlii)

|

| Top: Denslow’s Dorothy. Bottom: Neill’s Dorothy. |

In any

case, I generally preferred the later Oz books to the first one. Evan Schwartz writes: “Clearly, all of Baum’s Oz books derived

their magic from the original one, and nothing else that Frank created would

ever approach the brilliance of The

Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” (Finding Oz,

p. 297) But for me the Oz series in its

canonical form didn’t really get started until the third book, Ozma of Oz; I found its plot more

complex and engaging, its ideas more inventive, and its art (Neill’s) more

beautiful (though I appreciate Denslow’s art now much more than I did then –

particularly his exquisite sense of composition). Plus Dorothy seems to be enjoying herself,

and relishing her adventures in Oz, much more in the later books than in Wizard, where she is single-mindedly

focused on getting home. “I don’t like

your country, although it is so beautiful,” she tells the Wizard (ch. 11), and

“became very sad” and “would cry bitterly for hours” at the realization that “it

would be harder than ever to get back to Kansas.” (ch. 12) By contrast, when she is thrown overboard in

a chicken coop at the beginning of Ozma,

she takes the situation cheerfully in stride:

“Why, I’ve got a ship of

my own!” she thought, more amused than frightened at her sudden change of

condition ... Just now she was tossing

on the bosom of a big ocean, with nothing to keep her afloat but a miserable

wooden hen-coop that had a plank bottom and slatted sides, through which the

water constantly splashed and wetted her through to the skin! And there was

nothing to eat when she became hungry – as she was sure to do before long – and

no fresh water to drink and no dry clothes to put on. ... “Well, I declare!”

she exclaimed, with a laugh. “You’re in a pretty fix, Dorothy Gale, I can tell

you! and I haven’t the least idea how you're going to get out of it!” ... Many

children, in her place, would have wept and given way to despair; but because

Dorothy had encountered so many adventures and come safely through them it did

not occur to her at this time to be especially afraid. ... So she sat down in a

corner of the coop, leaned her back against the slats, nodded at the friendly

stars before she closed her eyes, and was asleep in half a minute. (Ozma,

ch. 1)

And when

she finds she has come ashore near Oz, her reaction is enthusiastic: “Dorothy clapped her hands together

delightedly. ... ‘I’m glad of that!’ she exclaimed. ‘It makes me quite happy to

be so near my old friends.’” (ch. 4) Indeed she is “anxious to see once more the

country where she had encountered such wonderful adventures.” (ch. 20)

Similarly, in a later book when Dorothy finds herself once again in Oz

with no clear way of getting home, she responds rather lightheartedly: “There isn’t so much to see in Kansas as

there is here, and I guess Aunt Em won’t be very

much worried; that is, if I don’t stay away too long." (Road,

ch. 3) The change from Denslow’s stolid

Dorothy to Neill’s lively one reflects the increased adventurousness with which

Baum endows Dorothy as the stories proceed.

(Yet according to Laura Miller, in the Oz books “[c]haracter is fixed,

and no one really changes.” Dorothy,

Miller complains, “remains exactly the same, ‘a simple, sweet and true little

girl,’ throughout the entire series.”

Note that Miller’s evidence is based on the narrator’s say-so rather

than on what actually happens in the books; as we’ll see, this is a common

problem with Baum’s critics. In claiming

that Oz characters never change, Miller also seems to have forgotten, e.g., the Wizard, and Jinjur, and the

Nome King.)

|

| Left: Denslow’s Dorothy & Wuizard. Right: Neill’s Dorothy & Wizard |

As for the

new Dorothy’s being prettier, given his preferred style Neill would probably

have done this anyway, but he may also have taken a cue from Baum’s text; in Ozma it is a crucial plot point that

Dorothy is “rather attractive,” since it explains why Princess Langwidere

covets her head (ch. 6), whereas Dorothy is never so described in Wizard. And while the move to a more conventionally

pretty and feminine Dorothy is potentially problematic from a feminist

perspective – in ways which were not on my radar at age six – the accompanying

move to a more intrepid and self-assured Dorothy is certainly a feminist plus.

So anyway,

that’s the story as to why it was Neill’s version of Dorothy that became my

vision of the character, which gave me one more reason for dissatisfaction with

the MGM version.

Today I

have greater appreciation for the 1939 movie’s artistic achievement; and I have

to admit that “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” (not in the

book) is one of the greatest lines in cinema history. Plus of course if I had seen the 1925 version,

the infidelities of the 1939 version would have seemed comparatively minor. (Indeed, Wizard

had been adapted for stage or screen half a dozen times before 1939, and the

MGM version was by far the most faithful of the lot.)

All the

same, for me Oz is: the later,

Neill-illustrated Oz books first; the first, Denslow-illustrated book second;

and the 1939 movie last.

So I still

find it annoying that the 1939 movie is most people’s first reference point for

Oz; that new Oz projects nearly always feature a Denslow/Garland-derived

Dorothy; and that even a book like Richard Tuerk’s Oz in Perspective, whose focus is on the novels rather than the

movie, still has it cover marred by an image of MGM’s goddamn ruby slippers. (They’re not even slippers, anyway; they’re

pumps. Why bother to change Baum’s

silver “shoes” to ruby “slippers” and yet not have them actually be slippers?)

Even

in scholarly articles by knowledgeable authors, the 1939 film manages to

insinuate itself whether reference to it makes sense or not. Jené

Gutierrez, for example, begins a recent article this way:

Since the film premiered in 1939, The Wizard of Oz has been the subject of numerous interpretations. In

1964, Henry Littlefield’s American

Quarterly essay entitled “The Wizard of Oz: Parable on Populism” espoused a

political connection, illustrating the story’s alignment with Populism. (“Psychospiritual Wisdom,” p. 54, in Durand

and Leigh, Universe of Oz, pp. 54-60)

The

clear implication of this passage is that Littlefield’s essay was proposing a

connection between populism and the MGM movie; but of course Littlefield’s

thesis, whatever its merits, was about the book, not the movie. Kevin Tanner, hypothesising a connection

between Dorothy’s silver shoes and the “silver slippers” in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, repeatedly refers to

Baum’s Dorothy herself as wearing slippers,

a term that comes solely from the movie.

(“Religious Populism and Spiritual Capitalism,” p. 211; in Durand and

Leigh, Universe, pp. 204-224) And I’ve lost track of how many discussions

of the book refer to Aunt Em as

“Auntie Em,” a nickname that likewise comes from the movie.

|

| The shadow of MGM |

The massive gravitational pull of the 1939 movie even manages to obscure the recollection of previous adaptations. Kevin Durand, who surely knows better, writes:

The canon of the universe of The Wizard of Oz ... can be divided roughly into two epochs –

pre-1939 and post-1939. Before the movie

roared into theatres, the Oz-verse was a purely literary one. L. Frank Baum’s books formed not only its

core, but its entirety. (“The Emerald Canon,” p. 11, in Durand and Leigh, Universe, pp. 11-23)

Here Durand consigns to the memory hole

three Oz stage musicals (at least one of which was a solid success, running for

293 performances on Broadway), eleven Oz movies (eight of which survive in some

form), and one Oz presentation that mixed film and live performance, all prior

to 1939.

Plus in

addition there’s the problem that the MGM movie apparently drives people

insane:

“Since 1939,” says Durand, “the movie

has set the stage for reading the book, not vice versa.” (“The Emerald Canon,” p. 11) Well, not here, mate.

As I’ve

mentioned, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

was illustrated by W. W. Denslow, while all of Baum’s subsequent Oz books were

illustrated by John R. Neill. Denslow

and Neill each did the art for several of Baum’s non-Oz books as well (indeed

Baum’s Sea Fairies arguably contains some

of Neill’s best work ever), and after Baum’s death Neill continued to provide

illustrations for works by new authors continuing the series (and even wrote

three himself). I griped about Denslow

above, but they’re both really good; and it’s

fascinating to contrast the bold strokes and stark simplicity of Denslow’s art with the

dense textures and feverish, proto-Seussian inventiveness of Neill’s.

Despite

their differences, both Denslow and Neill were clearly influenced by Art

Nouveau artists like Alfons Mucha – of whom Baum’s wife, at least, was a fan (Other Lands Than Ours, ch. 18) – with a

touch of influence from Pre-Raphaelites like J. W. Waterhouse as well, in Neill’s

case.

Note also

how on the accompanying cover from Jugend,

the Art Nouveau journal that gave Jugendstihl its name, the style looks as

though it’s halfway between Denslow and Neill:

The 1939

movie’s transition from black and white (or, originally, sepia) for Kansas to

Technicolor for Oz was anticipated by a 1933 cartoon; but the

idea really originates with Denslow’s colour scheme for the 1900 novel, where

the Kansas chapters are tinted in sepia tones, which give way to brighter

colours for the Oz chapters.

Baum

himself was not crazy about Neill’s work; at one point he called it

“perfunctory and listless,” and lacking a “spirit of fun” (quoted in Loncraine’s

Real Wizard, p. 270) – which is

perhaps the craziest thing ever said about Neill’s art.

|

| Perfunctory, listless, and lacking a spirit of fun? |

The best

versions available today appear to be those from Books of Wonder, which are

beautiful editions and have most of the illustrations (including colour plates);

however, these editions evidently delete some pictures, and also alter the

text, in order to censor some of Baum’s offensive racial stereotypes. (While I

sympathise with the motive, I don’t believe in censoring what children read or

see; far better to explain to children what’s wrong with certain things rather

than simply pretending they don’t exist.

At least that’s how I was raised, for which I am profoundly grateful.)

The Bradford recreations of the first editions are

presumably uncensored, if one is willing to shell out $50 a pop for them. But apparently even they have some missing

art, and have also botched what art they do have (see here, here, here, here,

and here). In short, there is no version

in print that does full justice to the art.

Not yet.

For my

information about Baum’s life, I rely primarily on four biographies: Katharine Rogers’ L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz, Rebecca Loncraine’s The Real Wizard of Oz: The Life and Times of L. Frank Baum, Nancy Koupal’s Baum’s Road to Oz: The Dakota Years, and Evan I. Schwartz’s Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story.

For my

information about Baum’s life, I rely primarily on four biographies: Katharine Rogers’ L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz, Rebecca Loncraine’s The Real Wizard of Oz: The Life and Times of L. Frank Baum, Nancy Koupal’s Baum’s Road to Oz: The Dakota Years, and Evan I. Schwartz’s Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story.

Each of

the four books has fascinating information the other three don’t, so none is

superfluous. But I must warn that the Schwartz book should be used with

caution. Schwartz has a tendency to

present speculation as though it were established fact. For example, he writes (p. 236) that Baum “continued

to suppress his guilt for his Aberdeen editorials against the Native Americans,

which was still a touchy subject with his mother-in-law” – when in fact we have

no evidence as to whether Baum regretted the editorials or indeed whether his

mother-in-law even knew of them. (More about those editorials next time.) Or

again, we’re told (p. 245) that Baum “would later allude to this critical point

of departure in his life [i.e. his

stint as a commercial traveler] by writing of the four companions as they

headed into the dangerous Winkie country to find the castle of the Wicked Witch

of the West” – despite there being no basis for knowing whether Baum intended any

such allusion; certainly one does not need to have been a travelling salesman

to come up with the idea of a difficult journey.

There are

also some puzzling errors. Schwartz quotes

(p. 101) as an in propria persona

political opinion of Baum’s a line Baum actually gives to one of his fictional

characters; he anachronistically attributes (p. 100) to Baum’s mother-in-law

Matilda Gage the use of the phrase “the religious right” when he is actually

quoting the modern scholar Sally Roesch Wagner; and in discussing the

revelation of the Wizard’s true nature he describes the version from the 1939

movie – saying that the humbug is “revealed when Toto notices something behind

a screen in the corner and essentially pulls away the curtain” (p. 280) – but

attributes it to Baum’s 1900 novel instead.

In fact what happens in Baum’s version is quite different: the Cowardly

Lion “gave a large, loud roar, which was so fierce and dreadful that Toto

jumped away from him in alarm and tipped over the screen that stood in a

corner.” (Wizard, ch. 15) In the book Toto does not “notice” the Wizard

or intentionally disclose him; the revelation is accidental.

Baum had

decided views on the appropriate content of children’s literature, and

presented his own works as exemplary of his preferred criteria. I’m

personally rather skeptical of “children’s literature” as a category; not every

good book for adults is suitable for children, to be sure, but as C.S. Lewis observes, any good book for children should be enjoyable for adults. In any case, Baum’s books do not reliably

follow his own advice.

For

example, Baum held that children’s stories should dispense with both descriptive

passages and love stories, since children, he thought, tended to be bored by

both. (This wasn’t true of me; at age

nine I was haunted by the opening descriptive lines of Dunsany’s Charwoman’s Shadow, and the female

pulchritude in Neill’s drawings was one of their chief attractions for me.) But there

are some fine descriptive passages in Baum’s work (the first chapter of Wizard being the most obvious example),

and several of his books contain love stories.

Baum also

criticises Dina Mulock’s book The Little Lame Prince for focusing on a disabled protagonist. With

proto-Randian severity, Baum explains that while perhaps “many crippled

children have derived a degree of comfort” from the book, “a normal child

should not be harrassed [sic] with pitiful subjects,” and “even the

maimed ones prefer to idolize the well and strong.”

Yet one of

Baum’s major recurring protagonists, Cap’n Bill, has an artificial leg; and

although he claims that his “wooden one was the best of the two,” Baum makes

clear that it is in fact an impediment to Bill’s full mobility:

Cap'n Bill's left leg

was missing, from the knee down, and that was why the sailor no longer sailed

the seas. The wooden leg he wore was good enough to stump around with on land,

or even to take Trot out for a row or a sail on the ocean, but when it came to “runnin’

up aloft” or performing active duties on shipboard, the old sailor was not

equal to the task. The loss of his leg had ruined his career and the old sailor

found comfort in devoting himself to the education and companionship of the

little girl. (Scarecrow of Oz, ch. 1)

Moreover, Baum

stresses Bill’s disability repeatedly.

His wooden leg is “not so useful on a downgrade as on a level, and he

had to be careful not to slip and take a tumble.” (Sea Fairies, ch. 2) “They could not go very

fast because the sailorman’s wooden leg was awkward to run with and held them

back” (Sky Island, ch. 11) “Cap’n Bill’s wooden leg would often go down

deep and stick fast in this mud, and at such times he would be helpless.” (ch.

17) He once “stepped his wooden leg into a hole in the ground and tumbled full

length.” (ch. 21) “It was no trouble for

the girl to keep her footing on the steep way, but Cap’n Bill, because of his

wooden leg, had to hold on to rocks and roots now and then to save himself from

tumbling.” (Scarecrow, ch. 1) He is

found “creeping along awkwardly because of his wooden leg,” and finds “hobbling

on a wooden leg all day ... tiresome.”

(ch. 3) “It was so difficult for Cap’n Bill to kneel

down, with his wooden leg.” (ch. 5) “I’m

not much good at [walking] because I've a wooden leg.” (ch. 8)

Cap’n

Bill’s brother, who is similarly one-legged, “began to stump toward the door,

but tripped his foot against his wooden leg and gave a swift dive forward,”

where he “would have fallen flat had he not grabbed the drapery at the doorway

and saved himself by holding fast to it with both hands,” but “rolled and

twisted ... awkwardly before he could get upon his legs,” prompting Trot to uncharacteristically

unkind laughter. (Scarecrow, ch. 14)

In a later

episode, Bill and Trot, the latter now apparently chastened by her own

temporary disability of being unable to move her feet from the ground, reflect

more generally on the issue:

“... I’m gett’n’ tired

standing here so long,” complained the girl. “If I could only lift one foot,

and rest it, I’d feel better.”

“Same with me, Trot.

I’ve noticed that if you’ve got to do a thing, and can’t help yourself, it gets

to be a hardship mighty quick.”

“Folks that can raise

their feet don’t appreciate what a blessing it is,” said Trot thoughtfully. “I

never knew before what fun it is to raise one foot, an’ then another, any time

you feel like it.”

“There’s lots o’ things

folks don't ’preciate," replied the sailor-man. “If somethin’ would ’most

stop your breath, you’d think breathin’ easy was the finest thing in life. When

a person’s well, he don’t realize how jolly it is, but when he gets sick he ’members

the time he was well, an’ wishes that time would come back. Most folks forget

to thank God for givin’ ’em two good legs, till they lose one o’ ’em, like I

did; and then it’s too late, ’cept to praise God for leavin’ one.” (Scarecrow,

ch. 15 – a rare mention of God in Baum’s writings.)

Cap’n Bill

is not presented as an object of pity; he lives a full life and makes important

contributions to the protagonists’ adventures.

All the same, Baum is inviting his able-bodied readers to empathise with

the difficulties of the disabled, and at the same time presenting his disabled

readers with a similarly disabled hero to admire – both things that Baum

elsewhere warns writers against.

When

Dorothy calls Cap’n Bill a “one-legged man,” Betsy Bobbin corrects her: he “isn’t

one-legged” but simply “has one wooden leg” (Scarecrow, ch. 21) – thus resisting Dorothy’s presumption that two-leggedness

must take a standard, “normal” form.

Dorothy retorts that having a wooden leg is “almost as bad” as being

genuinely one-legged; and it’s true, as we’ve seen, that Bill’s leg gives him

trouble. But Bill can also turn his

disability to advantage. He uses it to

rescue the Scarecrow: “Cap’n Bill had

the presence of mind to stick his wooden leg out over the water and the

Scarecrow made a desperate clutch and grabbed the leg with both hands.” (Scarecrow,

ch. 23) On a later occasion he uses it

as a weapon to impale a predator, who tells him: “If you hadn’t had a magic leg, instead of a

meat one, you couldn't have knocked me over so easily and stuck this wooden pin

through me.” (Magic, ch. 9) The wooden leg

also proves invulnerable to a spell that affects only flesh: “my wooden leg didn't take roots and grow,

either,” for “it’s only flesh that gets caught.” (ch. 10) What counts as a handicap is thus shown to be

context-relative.

Nor does

Baum’s engagement with the concerns of the disabled end here. As Joshua Eyler points out in “Disability and

Prosthesis in L. Frank Baum’s The

Wonderful Wizard of Oz” (Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 38.3 (Fall 2013), pp.

319-334), “the idea of disability unquestionably and powerfully appears as a

thematic current” throughout the first Oz book (the only one Eyler

considers): “From the well-known quest

for the brain, the heart, and the courage that Dorothy’s three companions

believe they are lacking, to the prosthetics they are given by the Wizard to

appease them, to the unusual chapter on the brittle residents of the Dainty

China Country, the novel’s use of disability is pervasive.”

Eyler

points out an odd passage in which Dorothy and her friends stay overnight in a

farmhouse on their way to the Emerald City.

Baum tells us, concerning the father of the household: “The man had hurt his leg, and was lying on

the couch in a corner.” (Wizard, ch. 10) As Eyler notes, Baum “jars the reader by

mentioning the man’s injury out of the blue and then never referring to it

again,” not even to tell “how the leg is injured or what caused the injury.”

Eyler suggests that Baum “intentionally constructs this passage in such an

ambiguous manner in order to set up the role disability will play in the

novel.”

“I do not

want people to call me a fool,” says the Scarecrow, explaining his desire for a

brain. (Wizard, ch. 3) Eyler

describes this as “an outward pressure, a construction of disability by society

that manifests itself as an intrinsic devaluing of his own importance,” and

notes that Baum “at every turn ... undercuts the Scarecrow’s socially constructed

disability by demonstrating that he already has that which others tell him

he is lacking.” Once the Scarecrow and

his companions receive their gifts from the Wizard, they have not “actually

changed in any way”; but “their prostheses have simply ameliorated the degree

to which they feel the weight of society’s disapprobation.” One would not have expected these sorts of

concerns from an author who had elsewhere insisted that children’s literature

should concern itself exclusively with the “normal,” the “well and strong,”

rather than with the “crippled” and “maimed.”

By

contrast, Burger accuses Baum of demonising “bodily difference” through “freak

discourse” (American Myth, p. 74),

because the Wicked Witch is ugly – as though bodily difference were not likewise

characteristic of the Tin Woodman, the Scarecrow, the Munchkins, and a good

many other positively depicted characters.

Admittedly,

Baum’s attitude toward difference can be hard to track. In one of the Oz books we’re told that “to be

different from your fellow creatures is always a misfortune” (Emerald City, ch. 8); and in another,

the normalisation of the Flatheads is presented as a desideratum: Glinda “caused the head to grow over the

brains – in the manner most people wear them – and they were thus rendered as

intelligent and good looking as any of the other inhabitants of the Land of Oz.” (Glinda,

ch. 24)

But

elsewhere Baum has the Scarecrow and the Cowardly Lion embrace diversity, at

least partly on elitist grounds:

I am convinced that the

only people worthy of consideration in this world are the unusual ones. For the

common folks are like the leaves of a tree, and live and die unnoticed. (Scarecrow, in Land, ch. 16)

Were we all like the

Sawhorse we would all be Sawhorses, which would be too many of the kind; were

we all like Hank, we would be a herd of mules; if like Toto, we would be a pack

of dogs; should we all become the shape of the Woozy, he would no longer be

remarkable for his unusual appearance. Finally, were you all like me, I would

consider you so common that I would not care to associate with you. To be individual, my friends, to be different

from others, is the only way to become distinguished from the common herd. Let

us be glad, therefore, that we differ from one another in form and in

disposition. Variety is the spice of life and we are various enough to enjoy

one another's society; so let us be content.

(Cowardly Lion, in Lost Princess,

ch. 10)

The

elitist aspect of the sentiment should probably not be taken too seriously;

Baum regularly satirises those who cultivate eccentricity solely in order to

feel superior to the majority:

People who are always

understood are very common. You are sure to respect those you can’t understand,

for you feel that perhaps they know more than you do. (Sea Serpent, Sea Fairies, ch. 5)

[A]s for doing anything,

there’s no use in it. All I meet are doing something, so I have decided it’s

common and uninteresting and I prefer to remain lonesome. (Lonesome Duck, Magic, ch. 15)

But the

endorsement of diversity may be sincere on Baum’s part even if the elitist

overtones are at least partly satirical.

|

| Boys and girls of every age, wouldn’t you like to see something strange? |

|

| Nothing scary to see here. Move along, move along. |

Four years later, in publicity for Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz, Baum elaborates:

I demanded fairy stories

when I was a youngster ... and I was a critical reader too. One thing I never

liked then, and that was the introduction of witches and goblins into the

story. I didn’t like the little dwarfs in the woods bobbing up with their

horrors. ... That’s why you’ll never find anything in my fairy tales which

frightens a child. I remember my own feelings well enough to determine that I

would never be responsible for a child’s nightmare. (Visitors,

p. 217.)

And he

adds elsewhere: “there should never be anything

except sweetness and happiness

in the Oz books, never a hint of

tragedy or horror” (quoted in Hearn, Annotated Wizard, p. xcv).

But it’s

hard to see how Baum could have said any of this with a straight face, inasmuch

as his work is – to his credit – filled

with creepy and frightening creatures and situations, which is one of the

reasons children love them. He clearly

knew that such material has uses other than to point morals, since he makes

entertaining use of them himself, usually with no moral attached – though he is

certainly capable of yoking them to heavy-handed sermonising on occasion,

despite his disclaimers. The Scarecrow

himself, though not scary in Baum’s treatment, had been based on a recurring

nightmare from Baum’s own childhood, showing that Baum clearly understood the

artistic potential of nightmares.

Moreover,

at the time that Baum made his remarks about not using witches, dwarves, and

goblins, he’d already put three wicked witches (East and West in Wizard, Mombi in Land) into the Oz books, and Nomes – surely a cross between dwarf

and goblin – would soon follow in Ozma.

|

| More cloying sweetness and happiness from Baum. |

All the

same, there is much to produce anxiety.

Baum continually emphasises the dependence, fragility, and vulnerability

of mere human flesh. In The Lost Princess of Oz, for example,

the Wooden Sawhorse says: “you are all

meat creatures, who tire unless they sleep, and starve unless they eat, and

suffer from thirst unless they drink.

Such animals must be very imperfect ....” (ch. 10) Likewise, the Patchwork Girl

remarks: “You're afraid ... because so

many things can hurt your meat bodies.”

(ch. 18)

Yet at the

same time Baum underlines the contingency of this dependence. Human beings can be transformed into nonmeat

materials as Nick Chopper is, losing old vulnerabilities – though at the same

time gaining new ones (e.g., Nick is vulnerable to rust, as the Scarecrow is to

fire; and we’ve seen that in replacing his leg with a wooden one, Cap’n Bill

likewise gains both advantages and disadvantages). But in any case, material embodiment is not

destiny: girls can be transformed into

boys (and back again), and royal families into bric-a-brac (and back again). Baum’s emphasis on corporeality coexists with

a gesture toward the transgender and the transhuman.

Anxieties

of material groundedness and vulnerability manifest in Baum’s economic realism,

from Uncle Henry’s mortgage problems in Emerald City and the financial anxieties of Aunt Jane’s Nieces, to the grinding poverty that pervades the tales in Mother Goose in Prose. Yet he can also, sometimes, imagine

post-scarcity utopias like Mo, Ev, and Oz, where, e.g., food grows on trees already cooked.

|

| This floating head is guaranteed to be not creepy at all. |

Examples

of body horror are equally plentiful in Baum’s non-Oz work: an animated mannequin gets her ear torn off

and her head caved in; a dragon is killed by stretching its body as thin as a

fiddlestring; a bruised and bleeding gopher has his tail cut off and sold for

two cents; a boy who is accidentally flattened by a clotheswringer must be

reinflated through a hole cut in his head;

a missionary is made into soap and cut into bars; a prince has to pluck out his own eye to

prevent it from taking over his mind; the Sky Islanders use people as living

pincushions, or punish them by splitting them in half and then mismatching the

halves; a “somewhat brittle” candy man falls downhill and is broken into

pieces, which his neighbours, also made of candy, promptly devour; one of the

candy people’s babies partially melts through being inadvertently left in the

sun; and Humpty-Dumpty lies “crushed and mangled among the sharp stones where

he had fallen,” while his friend Coutchie-Coulou is “crushed into a shapeless

mass by the hoof of one of the horses” as “her golden heart” is seen “spreading

itself slowly over the white gravel.”

As Vivian

Wagner writes: “Baum’s novels worry over bodies, animation, meat, and

survival.” (“Unsettling Oz,” p. 28; Lion and the Unicorn 30 (2006), pp.

25-53)

In light

of these passages, Baum’s insistence on a vast gulf between his kind of horror

and the kind that pervades, say, Grimm’s fairy tales is about as credible as

the distinction between good and bad taste in the 1954 testimony of Baum’s great successor, EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines, before the Senate

Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency:

Mr.

BEASER:

There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

Mr.

GAINES:

Only within the bounds of good taste.

Mr. BEASER: Your own good taste and salability?

Mr. GAINES: Yes.

Sen. KEFAUVER: Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Mr. GAINES: Yes, sir; I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

Sen. KEFAUVER: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

Mr. GAINES: A little.

C. S.

Lewis says, of those

who object to scary stories for children, that he himself “suffered too much

from night-fears ... in childhood to undervalue this objection.” Nevertheless, he worries that such objections

too often mean that we should “keep out of [the child’s] mind the knowledge

that he is born into a world of death, violence, wounds, adventure, heroism and

cowardice, good and evil.”

There is something

ludicrous in the idea of so educating a generation which is born to the Ogpu

and the atomic bomb. Since it is so likely that they will meet cruel enemies,

let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage. Otherwise you

are making their destiny not brighter but darker. Nor do most of us find that

violence and bloodshed, in a story, produce any haunting dread in the minds of

children. ... Let there be wicked kings and beheadings, battles and dungeons,

giants and dragons .... Nothing will persuade me that this causes an ordinary

child any kind or degree of fear beyond what it wants, and needs, to feel. For,

of course, it wants to be a little frightened.

As Rebecca

Loncraine points out, Baum’s interest in body horror may stem in part from his

own historical context:

The Civil War was one of

the first conflicts to use amputation on a large scale. ... People whom the

Baums knew before the war would have been recognizable but changed. Many men walked with a limp, with the aid of

a stick, and concealed prosthetics arms and legs beneath their clothes. ... One

veteran, Henry A. Barnum (no relation to P. T. Barnum), became widely known in

Syracuse in the years following the war, and young Frank Baum was sure to have

seen him. The veteran had been shot

through his side, and the bullet’s passage through him remained open. He displayed it as a curiosity, pushing a

long stick all the way through his flesh, following the line of the original

wound, as though he were made of dough ....

(Real Wizard, pp. 33-34)

An uneasy –

but at the same time playful – tension between bodily alteration as horror and

bodily alteration as salutary difference runs through Baum’s work. Nick Chopper’s fate, for example, initially

seems horrific, as his body is “chopped ... into several small pieces,” leaving

his “arms and legs and head” to be “picked up ... and made [into] a bundle.” But after all his parts have been replaced

with tin, he comes to consider “the tin head far superior to the meat one.” (Tin Woodman, ch. 2)

Not all of

Baum’s examples of body horror have such a silver (or tin) lining, however. This blog takes its name from a particularly disturbing

example originally intended for The Patchwork

Girl of Oz: “The Garden of Meats,”

in which conscious, ambulatory vegetables plant human children in the ground

and raise them for food. The sequence

was cut by the publisher’s request:

We are inclined to

believe it would be best to omit Chapter XXI, ‘The Garden of Meats.’ As we see

it, this chapter is not at all essential to the movement of the story, and we

do not think that the ideas therein are in harmony with your other fairy

stories. If this chapter remains in the book we should fear (and expect)

considerable adverse criticism. (Rogers,

Creator of Oz, p. 198)

– but not before Neill had illustrated it:

How could

Baum fill his stories with horror and still believe that they were

horror-free? Well, I’m inclined to think

he couldn’t. In particular, I have a

hard time imagining that he could sincerely slam the use of witches in

children’s stories without remembering that he had just written two good witches

and three wicked ones, with more on the way.

As I see

it, Baum was faced with a problem: the adults who buy books for children, and

the children who are supposed to end up reading them, are two different

audiences with different demands. The

difficulty was to deliver the goods to the second group, providing young

readers with the creepy thrills they quite properly wanted, while not getting

shut down by the gatekeepers from the first group, all too often in thrall to

insipid Victorian fantasies about the need to provide children with a diet of

sweetness-and-light mush.

|

| Alan Moore channels his inner Baum. |

As Baum wrote

in the newspaper he edited in Dakota Territory in the early 1890s:

There is no vice so

prevalent, nor one with which the public is more familiar, than that of

mercantile fabrications, or, more plainly, trade lies. It is the age of

deception and adulteration, and the people know it; yet they accept the most

preposterous statements of the purity and honesty of goods without emotion,

knowing at the same time that the gentle shopkeeper’s claims will not hold water.

Nor do they attach blame to the merchant, who is frequently well meaning and

who (outside his store) would scorn to utter an untruth or mislead his friends.

After giving the matter careful thought, we have arrived at the conclusion that

the public likes to have the goods they buy pronounced of superior quality ....

Merchants seldom acknowledge, even to themselves, the various devices employed

to hook a customer, or the deceptions practiced to make them believe in the

value of an article. ... Barnum was right when he declared the American people

liked to be deceived. At least they make no effort to defend themselves. The

merchants are less to blame than their customers .... (Aberdeen

Saturday Pioneer, 8 February 1890; quoted in Koupal, Baum’s Road, pp. 111-114)

Or

likewise, as he wrote in a later and better-known work:

Oz, left to himself,

smiled to think of his success in giving the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman and

the Lion exactly what they thought they wanted. “How can I help being a

humbug,” he said, “when all these people make me do things that everybody knows

can't be done? ...” (Wizard, ch. 16)

My guess

is that Baum sailed as close to the line as he thought he could get away with; when

the “Garden of Meats” chapter made what he was doing just a bit too obvious, he

backpedaled and assured his publisher: “I

am glad you objected to the 21st. chapter of The Patchwork Girl, for I do not like it myself.” Believe him if you like.

Unfortunately,

many of Baum’s critics seem to have fallen for the humbug. Gillian Avery, for example, writes:

[Baum] aimed ... to

exclude ‘all disagreeable incidents ... heartaches and nightmares’ and to

retain only ‘wonderment and joy’. ...

Those who have been reared from earliest childhood on the traditional European

tales expect shadow as well as light, are used to violence and the suffering

endured by the heroes and heroines as well as by the villains, and do not

expect these to be glossed over and eliminated – even when presented to children

.... The Wizard of Oz has the easy

optimism ... the message that nothing is unpleasant if you don’t want it to be;

together with a blandness that the European reader finds cloying. (Behold the Child: American Children and Their Books, 1621-1922, pp. 144-145)

And more

recently, Laura Miller has described Oz as a “sanitized” fantasy with no real

danger or fright. Evidently Baum’s

introductory remarks to Wizard act on

some readers as a kind of posthypnotic suggestion – or green spectacles –preventing

them from seeing horror and suffering even when they are plainly in the

text. (Avery also refers to the 1939

film as “a rare instance of a film that improves a book,” so there you go.)

Happily,

not all critics have been so easily taken in.

Richard Tuerk, for example, writes: “L. Frank Baum’s Oz books are richer

than most critics recognize. They are

also darker. Many critics seem to have

allowed Baum’s own statements about his intentions in his works to mislead

them.” (Oz in Perspective, p. 201) Katharine

Rogers notes that if Avery “had valued [Baum’s] books enough to read them with

attention, she would have found that they include both alarming perils and

recognition of human folly and evil.” (Creator of Oz, p. xvi) And the

great James Thurber sensibly observes:

I am glad that in spite

of his high determination, Mr. Baum failed to keep [the heartaches and

nightmares] out. Children love a lot of

nightmare and at least a little heartache in their books. And they get them in the Oz books. I know that I went through excruciatingly

lovely nightmares and heartaches when the Scarecrow lost his straw, when the

Tin Woodman was taken apart, when the Saw-Horse broke his wooden leg (it hurt

for me, even if it didn’t for Mr. Baum).

(quoted in Hearn, Annotated Wizard,

p. 7)

Thurber was

a man who could taste the difference between apple juice and hard cider.

Thurber

does seem to think, however, that the gap between theory and practice was inadvertent

on Baum’s part, a case in which he “failed” to live up to his “high

determination.” Burger likewise writes

that “Baum failed in this goal” (American Myth, p. 214), seemingly implying that he did nonetheless have such a goal. And Charity Gibson, while noting that “it is questionable

whether or not he succeeded in leaving out heartache and nightmares,” still

takes Baum at his word that “he was trying.” (“The

Wizard of Oz as a Modernist Work,” p. 110; in Durand & Leigh, Universe of Oz, pp. 107-118) As

noted above, I am rather more inclined to agree with Tuerk when he writes: “That so many nightmarish episodes could

result by accident or that Baum could have been unaware of them or their

implications seems preposterous.” (Oz in Perspective, p. 204) Rogers seems to express a similar skepticism. (Creator

of Oz, p. 265)

Before he

became a children’s writer, Baum worked inter

alia as an actor, a special-effects stage technician, a salesman and

ad-copy writer, and the editor of a journal devoted to methods for creating

alluring shop-window displays. He was a

master of presentation, of illusion, of misdirection. Of course he knew what he was doing. The only difference between Baum and his

wizardly creation is that the Wizard was concealing an innocuous reality behind

a hair-raising front, while Baum was concealing a hair-raising reality behind

an innocuous front. So which is truly

the greater and more terrible wizard?

[To be continued.

Next up:

Philosophy! Feminism! Fission!]

An outstanding piece, Roderick. I salute you. And I wonder if you've seen Gore Vidal's essay on the Oz books.

ReplyDeleteJR

Thanks! Are you the JR I know from the LL2 list or a different JR?

ReplyDeleteI haven't read Vidal's piece. Do you know of a copy that isn't behind a paywall?

Ah, just cross-correlated you with your Facebook self. Never mind the first question then.

DeleteThe essay is in two of his collections: The Second American Revolution and United States. I can't find it online except behind a paywall. And I'm Jeff Riggenbach, Roderick.

DeleteFANTASTIC page! I wrote in my blog about Neill and Denslow (mainly: http://pirlimpsiquices.blogspot.com.br/2013/09/grandes-ilustradores-john-r-neill.html), and I will gladly put the link of this text and research in it as a way of getting deeper into the series, the author, the ilustrations and all that is to that related. Congratulations for your great work!

ReplyDeleteI have one "theory" about the duel frightening images X Baum's intentions. For me it is a matter of perspective: Grimms's tales are scary because who suffers the dangers are always the heros, the children (well, most of the time); in Baum's work, the children and heroes are always "fixable" (if inanimates) or even safe almost every time (if of meat, like Dorothy, who never has bad injuries). The danger is more "caricature" than real. Like objects falling over cartoon characters, not real deaths or anything really spooky. That's how I see, and in this point Baum is not "lying" in his propositions.

Sorry for my not-so-good English. Greetings here from Brazil! :)